The Raga Kingdom

All these years of loving and appreciating Indian Classical music, I was thoroughly convinced that the development of thousands of profound ragas had basis only in deep spiritual and intellectual search of many a great individuals over countless millennia.

All these years of loving and appreciating Indian Classical music, I was thoroughly convinced that the development of thousands of profound ragas had basis only in deep spiritual and intellectual search of many a great individuals over countless millennia.

But some years ago, when I first came to know that a music system as profound as Indian Classical Raga system actually has its roots very firmly established in the folk music, I was at least a bit surprised. All these powerful ragas, capable of inducing altered states of mind and fabled to be powerful enough to call forth the rains or light up lamps, have originated from common man’s music!

Historically, the system of Indian classical music known as Raga Sangeet can formally be traced back more than two thousand years to its origin in the Vedic hymns of the Hindu temples, the fundamental source of all Indian classical music. Now what is a raga... well, it could be a hard thing to explain. There is an old adage in Sanskrit - "Ranjayati iti Ragah" - literally "that which colours the mind is a raga." For a raga to truly colour the mind of the listener, its effect must be created not only through the notes and the embellishments, but also by the presentation of these notes to carry the soul or mood of each raga.

Not Just a Scale

Though apparently following fixed modes, ragas should not be mistaken as mere modes or scales. A raga is a precise, subtle and profoundly aesthetic melodic form with its own peculiar ascending and descending movement consisting of either a full seven note octave, or a series of six or five notes (or a combination of any of these) in a rising or falling structure called the Arohana and Avarohana. It is the subtle difference in the order of notes, an omission of a dissonant note, an emphasis on a particular note, the slide from one note to another, and above all the underlying subtle mood or the soul, that distinguish one raga from another.

Shruti: Microtones

In an octave or saptak there are seven basic swaras or musical notes. Namely - Shadja, Rishabh, Gandhar, Madhyam, Pancham, Dhaivat and Nishad. These are shortened to and written as Sa, Ri or Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, and Ni or simply as S, R, G, M, P, D, N. On a closer look, there are 22 "shrutis" or microtones which comprise the octave or saptak in Indian system of music (as opposed to the 12 semitones in an octave in Western music). Use of the shruti's is unique to each raga. The application of the shruti's in conjunction with various ornamentation like "gamakas", "andolan" etc. incorporated in to "chalan" - or specific note patterns characteristic of the raga; its principle important note (vadi); the second important note (samavadi) result in to evoking the mood and emotional nuances peculiar to each.Time of Day - Raga Association

In addition to being associated with a particular mood, each raga, at least in the North Indian or Hindustani tradition, is also closely associated with a particular time of day or a season of the year. The day/night cycle is divided in eight equal intervals, called prahars. Each prahar - such as the time before dawn, noon, late afternoon, early evening, late night - is associated with a set of ragas.

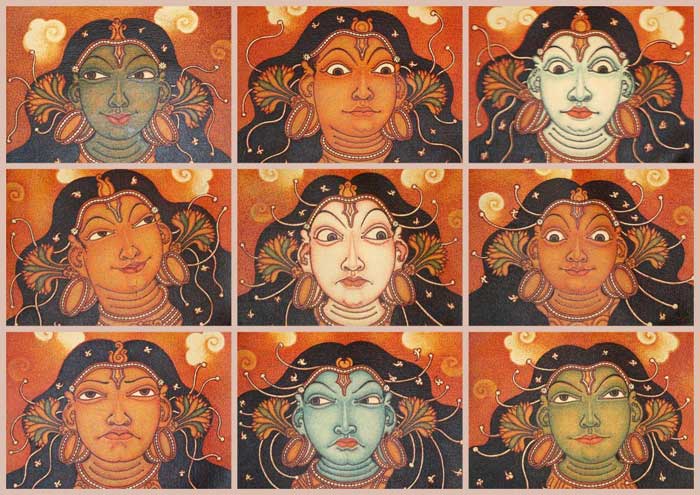

Nava Rasa: Nine Moods or Sentiments

The performing arts in India - music, dance, drama and poetry - are based on the concept of Nava Rasa, or the "nine sentiments". Literally, rasa means "juice" or "extract" but here in this context, we take it to mean "emotion" or "sentiment."

The acknowledged order of these sentiments is as follows:

- Shringara (romantic/erotic)

- Hasya (humorous)

- Karuna (pathos)

- Raudra (anger)

- Veera (heroic)

- Bhayanaka (horrific)

- Vibhatsa (disgustful)

- Adbhuta (amazing)

- Shanta (peaceful)

Each raga is principally dominated by one of these nine rasas, although the performer can also bring out other emotions in a less prominent way. The more closely the notes of a raga conform to the expression of one single idea or emotion, the more overwhelming the effect of the raga.

Ancient Classifications of Ragas

Through the ancient times, many music experts and scholars created their own way of classifing ragas. So much so that towards the end of the first millennium there were myriad number of classification systems in practice, often with conflicting ideas. Much of the basis of these classification was the Gramas (ancient tone systems) and Jatis (modes). A bit later there were prevalent a number of raga-ragini schemes. These primarily consisted of six 'male' patriarchal ragas, each with five or six 'female' raginis.Thaat System of Raga Classification

In the 16th century, Pundarika, a South Indian musicologist introduced the southern Mela (or scale types) system of classifying to Hindustani ragas Much later musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860-1936) adopted this system to create his own system of Raga classification - 'Thaat" based on ten heptatonic scale types.

A Thaat or framework was defined by Bhatkhande as a scale using all seven notes including Sa and Pa, with either the natural or alternate variety of each of the variable notes Re, Ga, Ma, Dha and Ni. In this system all ragas are classified under ten Thaats or scale types, each of which is named after a prominent raga which uses the note varieties in question.

The ten Thaats are:- Bilaval

- Khamaj

- Kafi

- Asavari

- Bhairavi

- Kalyan

- Todi

- Poorvi

- Marva

- Bhairav

More on this subject soon. So stay tuned!